As it’s coming up to Christmas, thought I’d repeat a

feel-good tale I wrote about a couple of years ago.

It was the middle of winter. John, Nigel and I had been

in Brest , France for over a month waiting for the

weather to give us the two day window of relative calm we required for crossing

the dreaded Bay of Biscay .

|

| Toekomst in Brest |

We were aboard the Toekomst, a sixty-five foot shrimp boat John had

bought in Holland

and our destination was Haiti

For many years mariners have rated Biscay as being

second only to Cape

Horn so far as general

nastiness is concerned. Huge swells roll in from North Atlantic storms and rise to massive heights

when they arrive at Biscay’s shelving sea bed. Many a vessel has gone to the

bottom of the dreaded Bay.

Whilst waiting for our window of calm in Brest

|

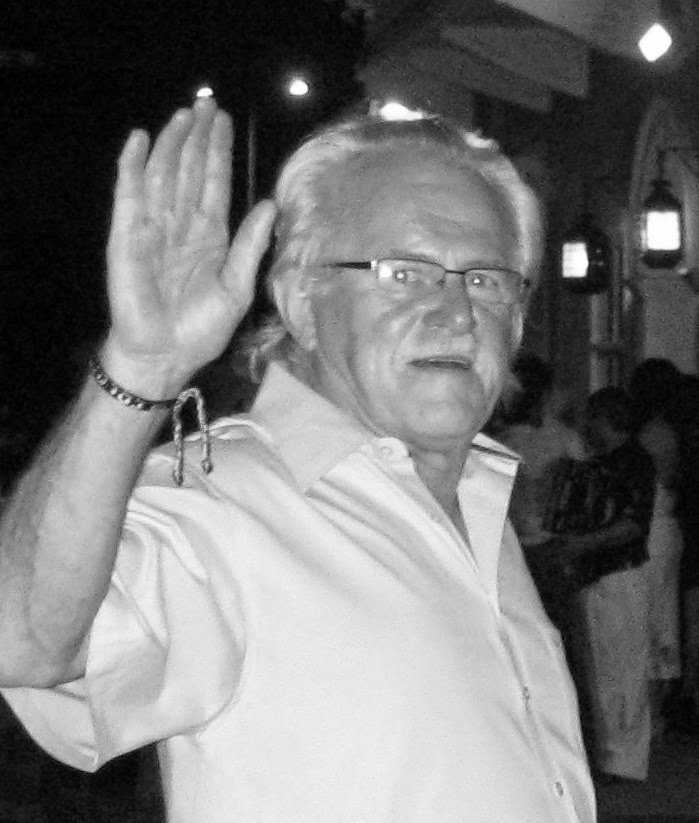

| Nigel, Me, John |

We were actually featured in a local newspaper when it

was discovered we planned to cross the Bay in the middle of winter. Fishermen

shook their heads at the stupidity of the English.

As it turned out though, the Bay was docile as a duck pond

for our crossing to La Coruña in Northern Spain .

.

It must have been around three in the morning when

Nigel shook me awake. John and I had consumed a few beers at a local bar to

celebrate our successful voyage and I was well out to it. “I think someone’s

fallen in the water,” Nigel announced. He’d apparently been up in the

wheelhouse having a smoke when he’d heard a splash, turned around and saw

ripples in the water.

Rather than deal with the matter himself (typical of

Nigel), he’d come below to rouse John and me and was convincing enough to lure

the two of us topsides into the freezing night. Leading us aft, he pointed to

the spot where he thought someone had fallen in. I peered

over the stern into the cold, inky water with dread.

After a few moments though, I managed to dredge up

sufficient courage to dive in and head for the bottom—some fifteen feet down.

I lucked out on my first dive: Feeling my way

along the muddy sea-bed I came upon a lump that felt like a body—which I

dragged to the surface.

The head of my limp, supposedly drowned victim had no

sooner cleared the water than it began jabbering away in Spanish. Frightened

the life out of me!

Despite my lack of knowledge of the foreign tongue it

was apparent that the words were not the product of a coherent mind. My new bottom-dwelling friend was obviously

drunk as a lord.

And as is the way of drunks, he was not at all

co-operative in my attempt to rescue him. With some difficulty, I managed to

get the rope John had thrown me around his chest, disengage myself and kick to a ladder set into the stone dock.

It took all three of us to drag the cheerfully

babbling Spaniard up the ten-foot dock wall. He was wearing a heavy coat and

didn’t appear to be suffering unduly from cold so we simply pointed him toward

town, gave him a shove and watched him toddle off up the road.

|

| In Antigua |

The whole episode still baffles me. According to

Nigel, when he heard the splash he turned around instantly and all he saw were ripples on the calm water, which meant that our friend must have gone down like

a rock.

Nigel then ran forward along the deck, descended the

companionway and shook John and me awake. So it had to have been three or four

minutes before I dove in and found the

body resting peacefully on the bottom.

Why wasn’t he thrashing around trying to get to the

surface? Why hadn’t he gulped down a lungful of water?

I have no idea.

Somehow though, our young friend managed to tuck away somewhere

in the recess of his inebriated mind, an accurate memory of the entire episode.

Later that day he and his mother arrived at the boat to thank us. He even

remembered me as the one who had pulled him up from the bottom.

A rather rotund Mom gave me a tearful bone-crushing

hug and a lengthy emotional speech, consisting mostly of, gracias, muchos gracias and mil gracias.

Peter’s such a

scavenger, you never know what he’ll pick up! Merry Christmas to all!. ~ Davina

PS: If you’ve any young adults in your family

(or are one yourself at heart), you might like to have a squizz at www.pblawson.com

.jpg)